Meet Little Amal, a 12 foot tall puppet of a 10 year old Syrian refugee. Here, she is welcomed in London in 2021 after completing a 5,000 mile journey across Europe. I’m excited to welcome her to my hometown in a week!

by Brigid Rowlings, LHI Communications Director

Little Amal, whose name means “hope” in Arabic, is a 12 foot tall puppet of a 10 year old Syrian refugee girl. She was created by Handspring Puppet Company to bring hope to refugees and displaced people around the world, especially children separated from their parents. She has traveled to more than 97 towns and cities in 15 countries and been welcomed by more than a million people. Her urgent message to us all is “Don’t forget about us.”

When I learned that Little Amal was coming to the United States, and was starting her journey right here in Boston, I wanted to find out how to be a part of welcoming her. I learned that the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) is a partner of Amal Walks Across America and is holding a series of workshops for the community to prepare for Amal’s arrival. Intrigued, I signed up for a session.

Yuna is excited to welcome Little Amal with an assortment of Amal’s favorite food: cookies!

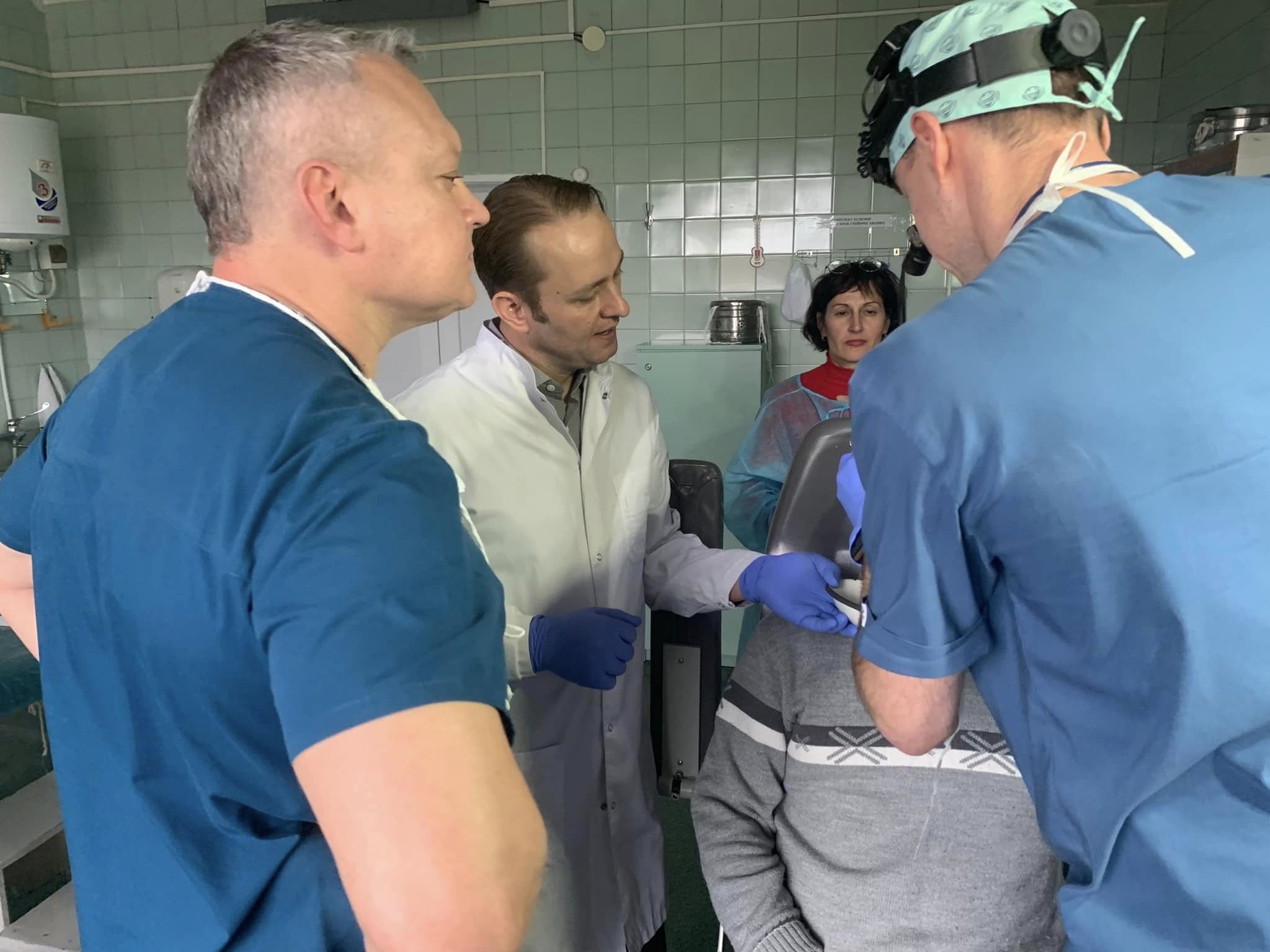

I arrived at the Harvard Ed Portal, a space for collaboration between Harvard University and the communities that surround it. I quickly met Yuna, age 4, and her sister Mina, age 2, who were there with their parents. Yuna had been reading books about refugees which is how she learned about Little Amal. Both girls were excited to tell the group that they’d seen a video of Little Amal’s appearance on the daytime TV program The View.

While Brisa Areli Muñoz, who is directing the Little Amal project for the A.R.T., led us through a poetry exercise, Yuna and Mila worked with Donya, a teaching artist at the A.R.T, to create posters to welcome Little Amal. What did the girls draw? Cookies! They’d learned from The View that cookies are Little Amal’s favorite food.

I was surprised and excited to find out that part of our role at the workshop that day was to think about what might happen when Little Amal approaches the gates to Harvard Yard. If you haven’t seen these gates in person or in photographs, they are a series of elaborate wrought iron gates spaced throughout a brick wall that surrounds Harvard Yard.

Brisa led our group through a conversation about what Little Amal’s approach to these gates might look like. We talked about the gates as a symbol for barriers—not only to Little Amal, but to many people who may not be able to access education, never mind the elite education of an Ivy League college. Emma, an A.R.T. student intern, shared that at night, the gates are locked and students must show their college ID to enter Harvard Yard. This led us to think about the importance of IDs and documents when crossing borders, and that some refugees and displaced people may not have had time to gather those items before fleeing their homes.

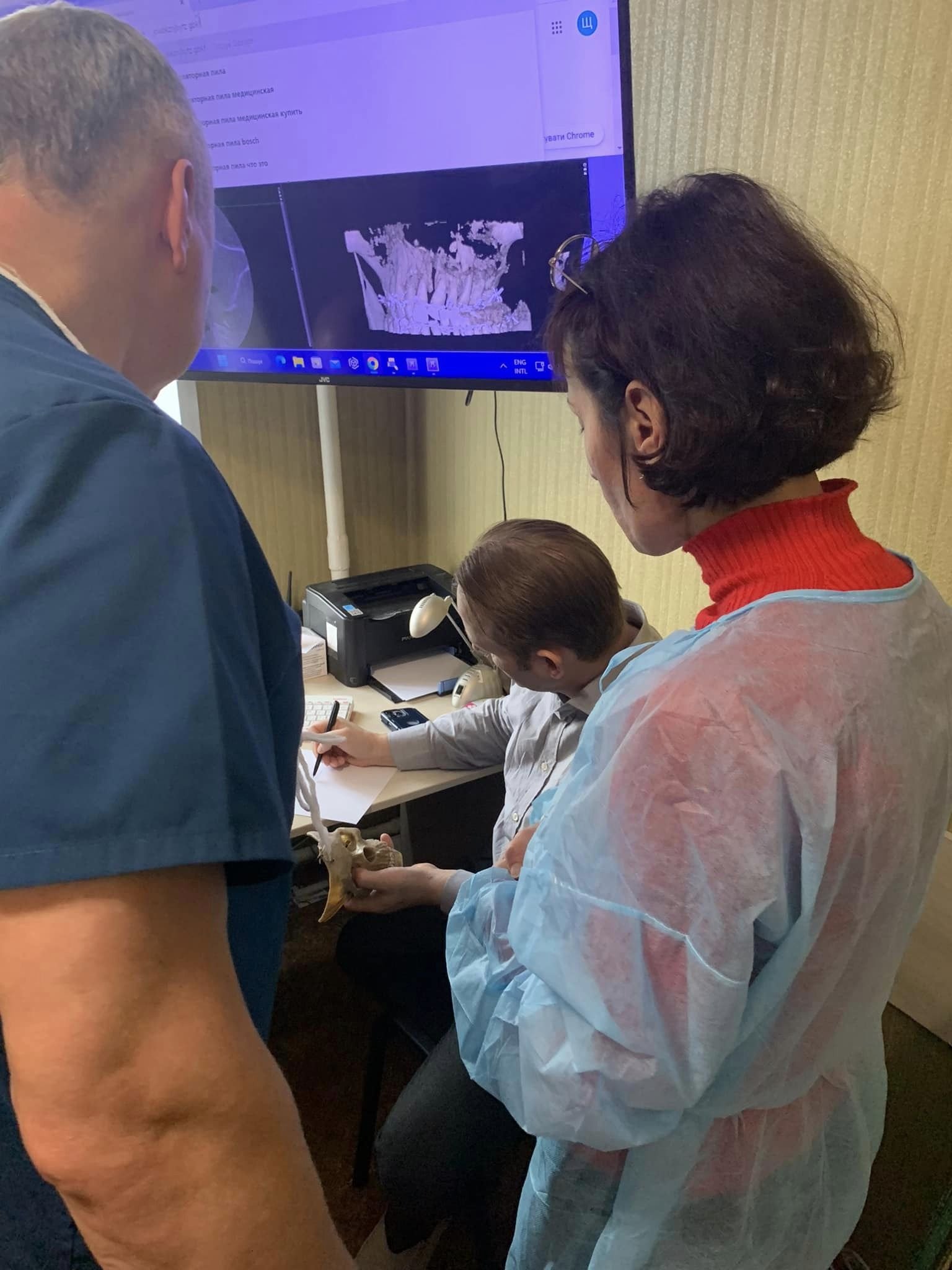

Ken, Emma, and Yolanda workshop a scene depicting Little Amal’s arrival at the gates of Harvard Yard. Thank you to the chairs for playing the role of the gate!

Then, Emma, Yolanda, a recent graduate of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Ken, a fellow community member, and I were tasked with coming up with possible ways Little Amal might interact with the gates to Harvard Yard. My group wanted the experience to communicate some truths about what refugees might experience. We came up with a scenario where Little Amal is turned away because she does not have an ID and can only enter when a person in power intervenes. A riff on this idea was one where two students collaborate to distract the security guard so that the ID-less Amal can sneak in.

My favorite idea, however, is that Little Amal sees a book floating through the Yard on the other side of the gates. She enters through the gates following the promises the book holds.

I think this is my favorite scenario because although my work at LHI has taught me so much about the challenges facing refugees and displaced people, it has also taught me through our library and education programs in Greece, our classroom program in Jordan, and our Storytime Project in Moldova, that stories, books, and learning offer hope and bring joy.

So, while I don’t know which direction Brisa and her team will take, I hope it is the magic book. I am excited to find out as I continue to participate in this project and welcome Little Amal on September 7!

To find out more about Lifting Hands International’s work with refugees and displaced people here in the United States and around the world, and how you can help us in this work, click here!